Rational Functions for MATH 140

Exam Relevance for MATH 140

Rational functions appear throughout MATH 140 for limits, derivatives, and curve sketching.

What Does "Rational" Actually Mean?

I know terminology can feel boring, but stick with me here — understanding the word rational will help you in many areas of math, not just this topic.

The word "rational" comes from ratio. A rational number is any number that can be written as a ratio of two integers — a fraction like $\frac{3}{4}$ or $\frac{-7}{2}$ or even $\frac{5}{1}$ (which is just 5).

So when mathematicians say rational function, they mean the same idea but with polynomials instead of integers: a ratio of two polynomials. That's it!

$$\text{Rational number} = \frac{\text{integer}}{\text{integer}} \qquad \text{Rational function} = \frac{\text{polynomial}}{\text{polynomial}}$$

Why does this matter? Because "rational" in math never means "logical" or "reasonable" (the everyday English meaning). It always means "can be expressed as a ratio." You'll see this word appear again and again:

- Rational numbers vs. irrational numbers (like $\pi$ and $\sqrt{2}$)

- Rational expressions in algebra

- Rational functions here in calculus

Once you see "rational = ratio," the name makes perfect sense, and you'll never forget what these functions are!

What is a Rational Function?

You just learned that polynomials are the "friendliest" functions in calculus — smooth, continuous, defined everywhere. But what happens when you divide one polynomial by another?

A rational function is a ratio of two polynomials:

$$f(x) = \frac{P(x)}{Q(x)}$$

where $P(x)$ and $Q(x)$ are both polynomials, and $Q(x) \neq 0$.

Think of it like a fraction, but instead of numbers in the numerator and denominator, you have polynomials. Just like you can't divide by zero with numbers, you can't let the denominator polynomial equal zero — and that's where things get interesting!

Examples:

- $f(x) = \frac{1}{x}$ — the simplest rational function

- $g(x) = \frac{x^2 - 1}{x + 3}$ — polynomial divided by polynomial

- $h(x) = \frac{2x + 5}{x^2 - 4}$ — linear over quadratic

Good news: Once you understand polynomials, rational functions are the natural next step. The main new idea is watching out for where the denominator equals zero — that's where all the action happens!

Why Rational Functions Matter in Calculus

After working with polynomials, you might wonder: why bother with rational functions? Can't we just stick with the friendly polynomials?

The reality is that many real-world relationships are naturally expressed as ratios. Think about:

- Rates: Speed is distance divided by time

- Concentrations: Amount of substance divided by volume

- Proportions: Part divided by whole

- Averages: Total divided by count

Whenever you divide one quantity by another, you're creating a ratio — and when those quantities involve variables, you often get a rational function.

In calculus, rational functions show up constantly because division is everywhere. And unlike polynomials, rational functions can have some interesting behaviors:

- Vertical asymptotes — where the function shoots to $\pm\infty$

- Holes — single missing points in an otherwise smooth curve

- Horizontal asymptotes — where the function levels off at the ends

- Domain restrictions — values of $x$ where the function simply doesn't exist

These features might seem like complications now, but they're actually what make rational functions useful for modeling real situations where things "blow up" or "level off."

Key Vocabulary

| Term | Meaning | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Rational function | A ratio of two polynomials $\frac{P(x)}{Q(x)}$ | $\frac{x^2 + 1}{x - 2}$ |

| Domain | All $x$ values where the function is defined | For $\frac{1}{x-3}$, domain is all $x \neq 3$ |

| Vertical asymptote | A vertical line $x = a$ where the function goes to $\pm\infty$ | $\frac{1}{x}$ has VA at $x = 0$ |

| Hole | A single point where the function is undefined but could be "filled in" | $\frac{x^2-1}{x-1}$ has a hole at $x = 1$ |

| Horizontal asymptote | A horizontal line $y = L$ that the function approaches as $x \to \pm\infty$ | $\frac{1}{x}$ has HA at $y = 0$ |

Examples of Rational Functions

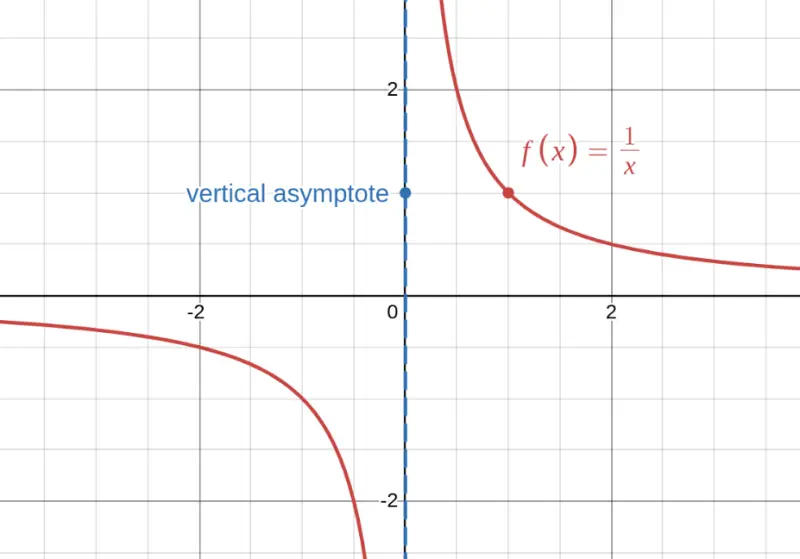

The simplest rational function: $f(x) = \frac{1}{x}$. Notice the vertical asymptote at $x = 0$ (where the denominator is zero) and the horizontal asymptote at $y = 0$ (the function approaches zero as $x$ gets huge).

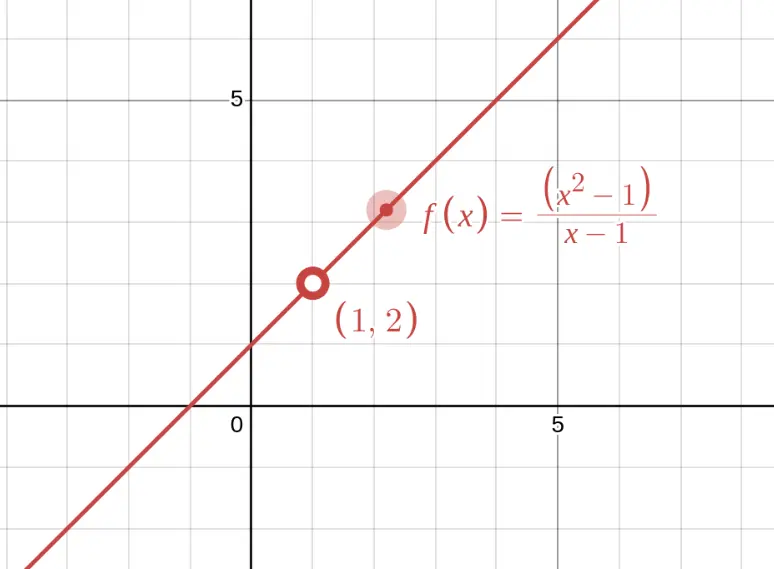

This looks like the line $y = x + 1$, but there's a hole at $x = 1$! Factor the numerator: $\frac{x^2-1}{x-1} = \frac{(x-1)(x+1)}{x-1}$. The $(x-1)$ cancels, but the original function is still undefined at $x = 1$.

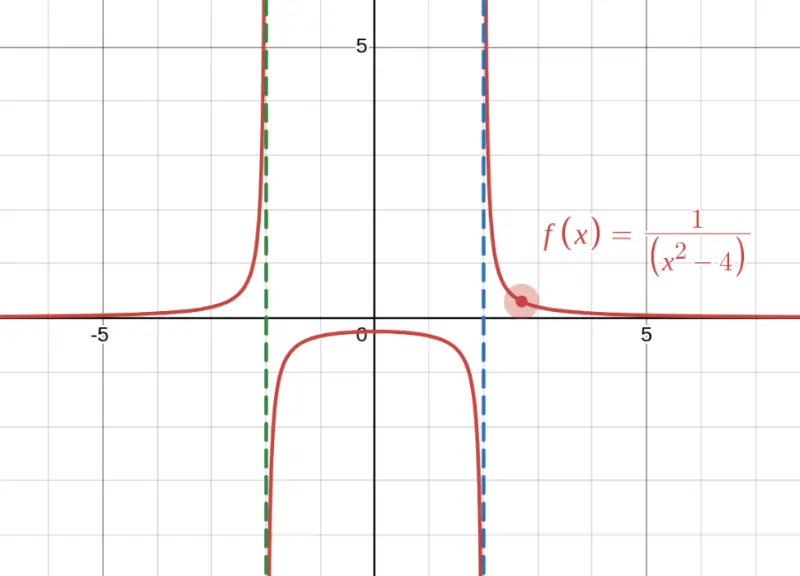

Here we have two vertical asymptotes at $x = -2$ and $x = 2$ (where $x^2 - 4 = 0$). The function shoots to $\pm\infty$ at both places.

Polynomials vs. Rational Functions

| Feature | Polynomials | Rational Functions |

|---|---|---|

| Domain | All real numbers | All reals EXCEPT where denominator = 0 |

| Vertical asymptotes | Never | Possible (where denominator = 0 and numerator ≠ 0) |

| Holes | Never | Possible (where both = 0 and factor cancels) |

| Horizontal asymptotes | Never | Often (depends on degrees) |

| End behavior | Always $\pm\infty$ | Can level off (HA) or go to $\pm\infty$ |

Key insight: Every polynomial IS a rational function (just put it over 1), but not every rational function is a polynomial!

Finding the Domain

The domain of a rational function is all real numbers except where the denominator equals zero.

Problem: Find the domain of $f(x) = \frac{3x + 1}{x - 5}$

Set denominator equal to zero: $x - 5 = 0 \Rightarrow x = 5$

$$\boxed{\text{Domain: all real numbers except } x = 5}$$

Problem: Find the domain of $g(x) = \frac{x}{x^2 - 9}$

Set denominator equal to zero: $x^2 - 9 = 0$

Factor: $(x-3)(x+3) = 0$

So $x = 3$ or $x = -3$

$$\boxed{\text{Domain: all real numbers except } x = 3 \text{ and } x = -3}$$

Problem: Find the domain of $h(x) = \frac{2x}{x^2 + 1}$

Set denominator equal to zero: $x^2 + 1 = 0$

This gives $x^2 = -1$, which has no real solutions!

$$\boxed{\text{Domain: all real numbers}}$$

This rational function has no vertical asymptotes or holes — the denominator is never zero for real $x$.

Vertical Asymptotes vs. Holes

When the denominator equals zero, you get either a vertical asymptote or a hole. Here's how to tell:

| If... | Then you have... |

|---|---|

| Denominator = 0 but numerator ≠ 0 | Vertical asymptote |

| Both numerator AND denominator = 0 (common factor) | Hole |

Problem: Analyze $f(x) = \frac{x + 2}{x - 3}$ at $x = 3$

At $x = 3$:

- Denominator: $3 - 3 = 0$ ✓

- Numerator: $3 + 2 = 5 \neq 0$

Since only the denominator is zero, there's a vertical asymptote at $x = 3$.

Problem: Analyze $g(x) = \frac{x^2 - 4}{x - 2}$ at $x = 2$

At $x = 2$:

- Denominator: $2 - 2 = 0$ ✓

- Numerator: $4 - 4 = 0$ ✓

Both are zero! Factor: $g(x) = \frac{(x-2)(x+2)}{x-2}$

The $(x-2)$ cancels, leaving $g(x) = x + 2$ (for $x \neq 2$).

There's a hole at $x = 2$, and the $y$-value of the hole is $2 + 2 = 4$.

Horizontal Asymptotes (End Behavior)

How does a rational function behave as $x \to \pm\infty$? It depends on the degrees of the numerator and denominator.

Let $n =$ degree of numerator, $m =$ degree of denominator:

| Comparison | Horizontal Asymptote | Example |

|---|---|---|

| $n < m$ | $y = 0$ | $\frac{1}{x^2}$ → HA at $y = 0$ |

| $n = m$ | $y = \frac{\text{leading coeff of } P}{\text{leading coeff of } Q}$ | $\frac{3x^2}{2x^2} \to$ HA at $y = \frac{3}{2}$ |

| $n > m$ | No horizontal asymptote (goes to $\pm\infty$) | $\frac{x^3}{x}$ → no HA |

Memory trick:

- Bottom heavy ($n < m$): squashes to zero

- Equal degrees ($n = m$): ratio of leading coefficients

- Top heavy ($n > m$): blows up (no HA)

Problem: Find the horizontal asymptote of $f(x) = \frac{4x^2 - x + 1}{2x^2 + 5}$

Degree of numerator: 2 Degree of denominator: 2

Since $n = m$, the HA is the ratio of leading coefficients:

$$y = \frac{4}{2} = 2$$

$$\boxed{\text{Horizontal asymptote: } y = 2}$$

What is NOT a Rational Function?

A function is not a rational function if it contains:

- Roots or fractional powers of $x$ — like $\sqrt{x}$ or $x^{1/3}$

- Transcendental functions — like $\sin x$, $e^x$, $\ln x$

- Variables in exponents — like $2^x$

✗ NOT Rational Functions:

- $f(x) = \frac{\sqrt{x}}{x + 1}$ — numerator has $\sqrt{x} = x^{1/2}$ (not a polynomial)

- $g(x) = \frac{\sin x}{x}$ — numerator is trigonometric (not a polynomial)

- $h(x) = \frac{e^x}{x^2 + 1}$ — numerator is exponential (not a polynomial)

✓ ARE Rational Functions:

- $f(x) = \frac{x^3 - 2x}{x^2 + 1}$ — both parts are polynomials ✓

- $g(x) = x^2 + 3x - 5$ — this is $\frac{x^2 + 3x - 5}{1}$ ✓

- $h(x) = 7$ — this is $\frac{7}{1}$ ✓

Practice: Classify and Analyze

Problem: Is $f(x) = \frac{x^2 + 1}{x^3 - x}$ a rational function? If so, find its domain.

Both numerator ($x^2 + 1$) and denominator ($x^3 - x$) are polynomials. ✓

For domain, set denominator = 0: $x^3 - x = 0$ $x(x^2 - 1) = 0$ $x(x-1)(x+1) = 0$

So $x = 0$, $x = 1$, or $x = -1$

$$\boxed{\text{Yes, rational function. Domain: all } x \neq 0, 1, -1}$$

Problem: Does $g(x) = \frac{2x + 1}{x^2 + 4}$ have any vertical asymptotes?

Set denominator = 0: $x^2 + 4 = 0$

This gives $x^2 = -4$, which has no real solutions.

$$\boxed{\text{No vertical asymptotes}}$$

Problem: Find all asymptotes of $h(x) = \frac{3x - 6}{x - 4}$

Vertical asymptote: Set $x - 4 = 0 \Rightarrow x = 4$

Check numerator at $x = 4$: $3(4) - 6 = 6 \neq 0$, so it's a VA (not a hole).

Horizontal asymptote: Degree of top = 1, degree of bottom = 1.

Since degrees are equal: $y = \frac{3}{1} = 3$

$$\boxed{\text{VA: } x = 4, \quad \text{HA: } y = 3}$$

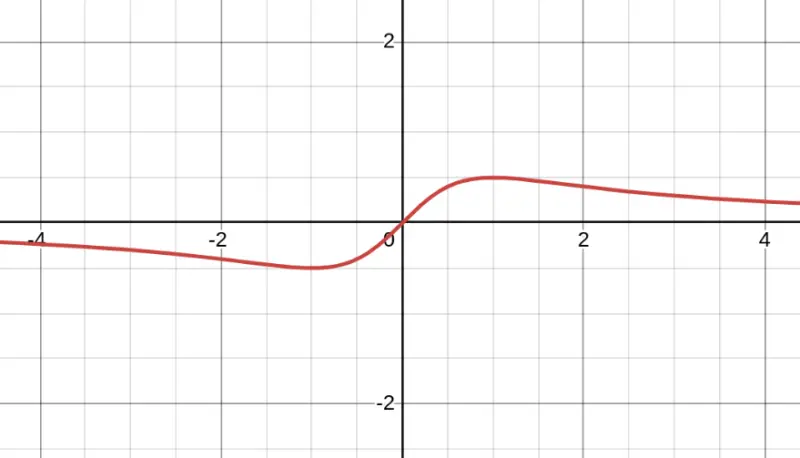

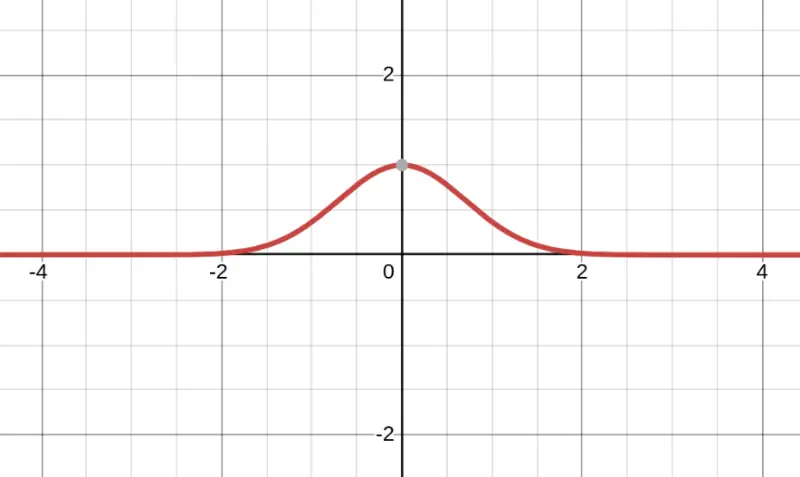

Problem: Is it possible that this graph represents a rational function?

Yes! Check the features:

- ✓ Smooth curve (rational functions are smooth except at asymptotes/holes)

- ✓ Horizontal asymptote at $y = 0$ (consistent with degree of numerator < degree of denominator)

- ✓ No vertical asymptotes (denominator could be always positive, like $x^2 + 1$)

- ✓ Defined for all $x$ shown

This could be something like $\frac{x}{x^2 + 1}$.

$$\boxed{\text{Yes, this could be a rational function}}$$

Problem: Is it possible that this graph represents a rational function?

No! This curve approaches $y = 0$ on both sides (as $x \to +\infty$ AND $x \to -\infty$), which is fine. But look more carefully — this is a "bell curve" shape that peaks and then decays.

A rational function with HA at $y = 0$ must have the numerator degree less than the denominator degree. But such functions approach the asymptote monotonically (from one direction) — they don't have this symmetric "bump" shape.

This is actually $e^{-x^2}$, an exponential function (not rational).

$$\boxed{\text{No, this cannot be a rational function}}$$

Common Mistakes and Misunderstandings

❌ Mistake: Canceling changes the function

Wrong: "$\frac{x^2 - 1}{x - 1} = x + 1$ everywhere"

Why it's wrong: While you CAN simplify by canceling $(x-1)$, the original function is still undefined at $x = 1$. Canceling doesn't remove the hole!

Correct: $\frac{x^2 - 1}{x - 1} = x + 1$ for all $x \neq 1$. At $x = 1$, the original function has a hole.

❌ Mistake: Vertical asymptote means the function equals infinity

Wrong: "At $x = 2$, $f(x) = \frac{1}{x-2}$ equals infinity"

Why it's wrong: Infinity is not a number. The function is undefined at $x = 2$ — it doesn't equal anything there.

Correct: As $x$ approaches 2, $f(x)$ grows without bound (approaches $+\infty$ or $-\infty$). But $f(2)$ does not exist.

❌ Mistake: Every zero of the denominator is a vertical asymptote

Wrong: "The function $\frac{x-3}{x-3}$ has a vertical asymptote at $x = 3$"

Why it's wrong: At $x = 3$, BOTH the numerator and denominator are zero. This means the factor $(x-3)$ cancels, leaving a hole, not an asymptote.

Correct: $\frac{x-3}{x-3} = 1$ for $x \neq 3$. There's a hole at $x = 3$, not a vertical asymptote.

❌ Mistake: Confusing horizontal asymptotes with limits at specific points

Wrong: "The horizontal asymptote tells us what happens at $x = 0$"

Why it's wrong: Horizontal asymptotes describe end behavior — what happens as $x \to \pm\infty$. They say nothing about what happens at $x = 0$ or any other specific point.

Correct: To find $f(0)$, substitute $x = 0$ into the function. The horizontal asymptote only describes the function's behavior "at infinity."

This skill is taught in the following courses. Create an account to access practice exercises and full course materials.