Logarithmic functions for MATH 140

Exam Relevance for MATH 140

Logarithmic functions are used throughout MATH 140. Know log properties for simplification before differentiating.

The Spotify Problem

Imagine you're an engineer at a music streaming platform. Your boss wants a simple 5-tier ranking system for songs: Bronze, Silver, Gold, Platinum, and Diamond.

The data team reports that song play counts range from 1 play (your roommate's SoundCloud demo) to 10 billion plays (global mega-hits like "Blinding Lights").

"Easy," you think. "We'll divide it evenly — 2 billion plays per tier."

| Tier | Play Range |

|---|---|

| Bronze | 0 - 2 billion |

| Silver | 2 - 4 billion |

| Gold | 4 - 6 billion |

| Platinum | 6 - 8 billion |

| Diamond | 8 - 10 billion |

Then you test it:

- Your roommate's demo (12 plays) → Bronze

- A local band's regional hit (50,000 plays) → Bronze

- A chart-topping single (5 million plays) → Bronze

- A viral TikTok song (500 million plays) → Bronze

Wait... 99.9% of all songs are Bronze? The tier system is useless.

The problem: these play counts span 10 orders of magnitude (from 1 to 10,000,000,000). A linear scale crushes all the "small" values together.

The Fix: Think Multiplicatively

What if each tier represented a ×100 jump instead of a +2 billion jump?

| Tier | Play Range |

|---|---|

| Bronze | 1 - 100 plays |

| Silver | 100 - 10,000 plays |

| Gold | 10,000 - 1 million plays |

| Platinum | 1 million - 100 million plays |

| Diamond | 100 million - 10 billion plays |

Now:

- Your roommate's demo (12 plays) → Bronze

- Local band's regional hit (50,000 plays) → Gold

- Chart-topping single (5 million plays) → Platinum

- Viral TikTok song (500 million plays) → Diamond

Each tier represents a meaningful level of success. Going from 100 to 10,000 plays is the same "jump" as going from 1 million to 100 million — both are ×100.

This is logarithmic thinking. Instead of asking "how much more?", we ask "how many times more?"

The Connection to Exponentials

In the last lesson, you saw exponential growth: a penny doubled daily becomes $10.7 million. The question was "start with a base, apply the exponent, what do you get?"

But what if you flip the question?

Exponential: "A song has 10,000 plays. If plays increase 10× per tier, what tier is it?"

Logarithmic: "I know the result (10,000) and the multiplier (10). What's the tier number?"

That tier number — the exponent you need — is exactly what a logarithm tells you.

$$\log_{10}(10{,}000) = 4$$

The song is in tier 4. Logarithms answer: "What exponent do I need to reach this number?"

What is a Logarithm?

A logarithm answers the question: "What exponent do I need?"

$$\log_a(x) = y \quad \text{means} \quad a^y = x$$

Read $\log_a(x)$ as "log base $a$ of $x$."

The key insight: Logarithms and exponentials are two ways of expressing the same relationship:

| Exponential Form | Logarithmic Form | In words |

|---|---|---|

| $2^3 = 8$ | $\log_2(8) = 3$ | "2 to what power gives 8? Answer: 3" |

| $10^2 = 100$ | $\log_{10}(100) = 2$ | "10 to what power gives 100? Answer: 2" |

| $5^4 = 625$ | $\log_5(625) = 4$ | "5 to what power gives 625? Answer: 4" |

| $e^1 = e$ | $\ln(e) = 1$ | "e to what power gives e? Answer: 1" |

Think of it this way:

- Exponential: You know the exponent, you want the result

- Logarithm: You know the result, you want the exponent

The Two Most Important Logarithms

While you can have a logarithm with any positive base (except 1), two bases dominate:

Common Logarithm (Base 10)

$$\log_{10}(x) = \log(x)$$

When you see "$\log$" with no base written, it usually means base 10. This is the "common logarithm."

Why base 10? Because we use a decimal number system!

- $\log(10) = 1$ (one zero)

- $\log(100) = 2$ (two zeros)

- $\log(1000) = 3$ (three zeros)

- $\log(1{,}000{,}000) = 6$ (six zeros)

The common logarithm essentially counts "how many digits minus one" or "what order of magnitude."

Natural Logarithm (Base $e$)

$$\log_e(x) = \ln(x)$$

The natural logarithm uses base $e \approx 2.71828$ and is written as "$\ln$" (from the Latin logarithmus naturalis).

Why is this "natural"? In calculus, $\ln(x)$ has the beautiful property:

$$\frac{d}{dx}[\ln(x)] = \frac{1}{x}$$

No other logarithm has such a clean derivative. This makes $\ln(x)$ the go-to logarithm for calculus, just like $e^x$ is the go-to exponential.

Converting Between Forms

The ability to switch between exponential and logarithmic forms is essential. Practice this until it's automatic:

From Exponential to Logarithmic

$$a^y = x \quad \Longrightarrow \quad \log_a(x) = y$$

The base stays the base. The exponent becomes the answer. The result becomes the input.

Examples:

- $3^4 = 81 \quad \Longrightarrow \quad \log_3(81) = 4$

- $e^2 \approx 7.389 \quad \Longrightarrow \quad \ln(7.389) \approx 2$

- $10^{-1} = 0.1 \quad \Longrightarrow \quad \log(0.1) = -1$

From Logarithmic to Exponential

$$\log_a(x) = y \quad \Longrightarrow \quad a^y = x$$

Examples:

- $\log_2(32) = 5 \quad \Longrightarrow \quad 2^5 = 32$

- $\ln(1) = 0 \quad \Longrightarrow \quad e^0 = 1$

- $\log_5(125) = 3 \quad \Longrightarrow \quad 5^3 = 125$

The Graph of a Logarithmic Function

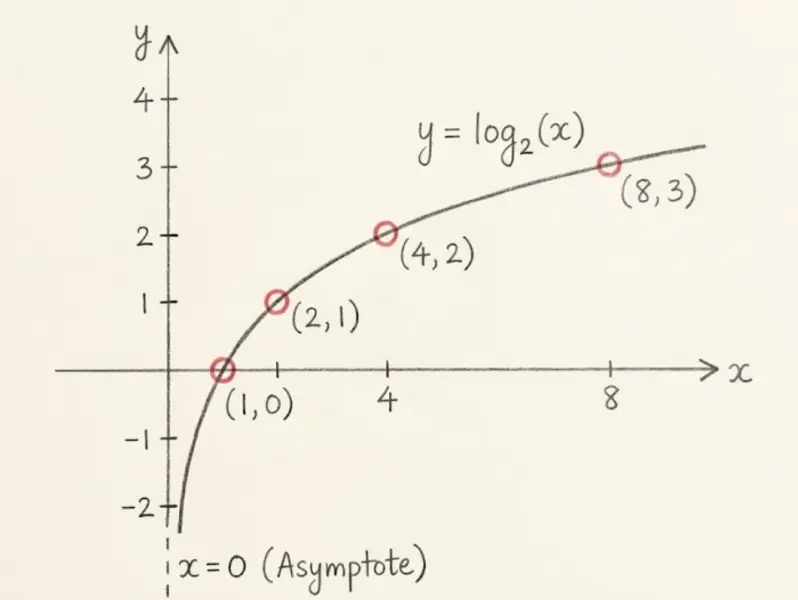

Let's visualize $f(x) = \log_2(x)$ by building a table:

| $x$ | $\log_2(x)$ | Because... |

|---|---|---|

| 1/8 | -3 | $2^{-3} = 1/8$ |

| 1/4 | -2 | $2^{-2} = 1/4$ |

| 1/2 | -1 | $2^{-1} = 1/2$ |

| 1 | 0 | $2^0 = 1$ |

| 2 | 1 | $2^1 = 2$ |

| 4 | 2 | $2^2 = 4$ |

| 8 | 3 | $2^3 = 8$ |

| 16 | 4 | $2^4 = 16$ |

Notice the shape: it rises steeply at first, then grows more and more slowly. This is the opposite of exponential growth!

Logarithms and Exponentials are Inverses

Here's the profound relationship: logarithms and exponentials undo each other.

$$\log_a(a^x) = x \quad \text{and} \quad a^{\log_a(x)} = x$$

Think of it like this:

- $\sqrt{\ }$ undoes squaring: $\sqrt{x^2} = x$

- $\log_a$ undoes $a^x$: $\log_a(a^x) = x$

Graphically, this means the graphs of $y = a^x$ and $y = \log_a(x)$ are reflections of each other across the line $y = x$.

This reflection swaps:

- Domain and range

- Horizontal and vertical asymptotes

- The roles of $x$ and $y$

| Property | $f(x) = 2^x$ | $g(x) = \log_2(x)$ |

|---|---|---|

| Domain | All real numbers | $(0, \infty)$ |

| Range | $(0, \infty)$ | All real numbers |

| Asymptote | Horizontal: $y = 0$ | Vertical: $x = 0$ |

| Key point | $(0, 1)$ | $(1, 0)$ |

| Behavior | Always increasing | Always increasing |

Key Properties of Logarithmic Functions

For $f(x) = \log_a(x)$ where $a > 0$ and $a \neq 1$:

| Property | What it means |

|---|---|

| Domain | $(0, \infty)$ — only positive inputs! |

| Range | All real numbers — outputs can be anything |

| $x$-intercept | Always $(1, 0)$ because $\log_a(1) = 0$ |

| Vertical asymptote | $x = 0$ (approaches but never touches the $y$-axis) |

| Always increasing or decreasing | If $a > 1$: always increasing. If $0 < a < 1$: always decreasing |

| One-to-one | Each $y$ value comes from exactly one $x$ value |

Why can't we take the log of zero or negative numbers?

Think about it: $\log_2(0) = ?$ would mean $2^? = 0$. But no power of 2 ever equals zero!

And $\log_2(-8) = ?$ would mean $2^? = -8$. But $2^x$ is always positive!

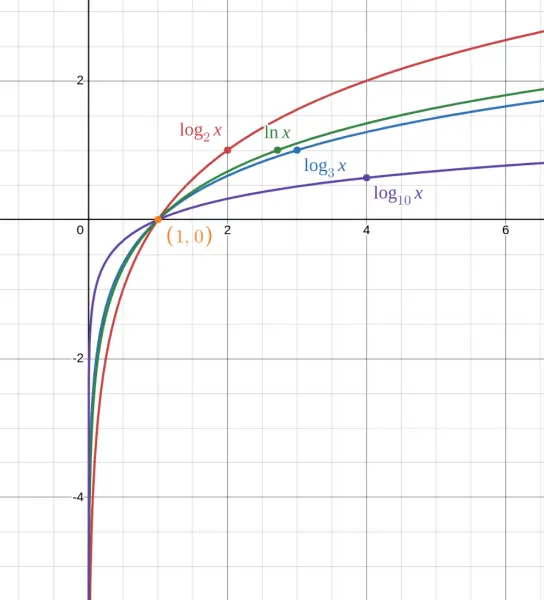

Notice that ALL these curves pass through $(1, 0)$. That's because $a^0 = 1$ for any positive $a$, so $\log_a(1) = 0$.

Special Values to Memorize

These show up constantly — know them cold:

| Expression | Value | Why |

|---|---|---|

| $\log_a(1)$ | $0$ | Because $a^0 = 1$ |

| $\log_a(a)$ | $1$ | Because $a^1 = a$ |

| $\log_a(a^n)$ | $n$ | Logarithm undoes the exponential |

| $\ln(1)$ | $0$ | Because $e^0 = 1$ |

| $\ln(e)$ | $1$ | Because $e^1 = e$ |

| $\log(10)$ | $1$ | Because $10^1 = 10$ |

| $\log(100)$ | $2$ | Because $10^2 = 100$ |

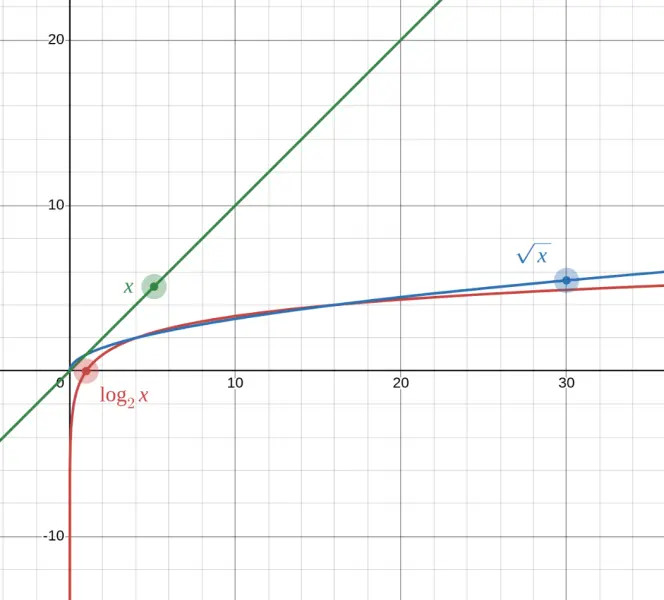

Logarithmic vs. Exponential Growth

Logarithms grow incredibly slowly compared to other functions.

| $x$ | $\log_2(x)$ | $\sqrt{x}$ | $x$ |

|---|---|---|---|

| 4 | 2 | 2 | 4 |

| 16 | 4 | 4 | 16 |

| 256 | 8 | 16 | 256 |

| 65,536 | 16 | 256 | 65,536 |

| 1,000,000 | ~20 | 1,000 | 1,000,000 |

To get $\log_2(x) = 20$, you need $x = 2^{20} = 1{,}048{,}576$ — over a million!

This slow growth is actually useful! It's why we use logarithmic scales:

- Decibels (sound intensity) — lets us compare a whisper to a jet engine

- Richter scale (earthquakes) — a magnitude 8 is 10× more intense than magnitude 7

- pH scale (acidity) — each unit is a 10× change in hydrogen ion concentration

Why Logarithms Matter in Real Life

The Decibel Scale

Sound intensity varies enormously. A jet engine is about 1,000,000,000,000 times more intense than the quietest sound you can hear. That's unwieldy!

Instead, we use decibels: $dB = 10 \log\left(\frac{I}{I_0}\right)$

| Sound | Intensity ratio | Decibels |

|---|---|---|

| Threshold of hearing | 1 | 0 dB |

| Whisper | 100 | 20 dB |

| Normal conversation | 1,000,000 | 60 dB |

| Jet engine | 1,000,000,000,000 | 120 dB |

Logarithms compress huge ranges into manageable numbers!

The Richter Scale

Earthquake magnitude: $M = \log\left(\frac{A}{A_0}\right)$

Each whole number increase means 10× more ground shaking. A magnitude 8 earthquake releases about 32 times more energy than a magnitude 7.

Computer Science

Logarithms appear everywhere in algorithms:

- Binary search takes $\log_2(n)$ steps to find an item in a sorted list of $n$ items

- Efficient sorting algorithms take about $n \log(n)$ operations

If you have 1 billion items, binary search finds any item in about $\log_2(1{,}000{,}000{,}000) \approx 30$ steps. That's the power of logarithmic efficiency!

Practice: Evaluate and Convert

Problem: Evaluate $\log_3(81)$

Ask yourself: "3 to what power equals 81?"

$3^1 = 3$ $3^2 = 9$ $3^3 = 27$ $3^4 = 81$ ✓

$$\boxed{\log_3(81) = 4}$$

Problem: Evaluate $\log_5\left(\frac{1}{25}\right)$

Ask: "5 to what power equals $\frac{1}{25}$?"

We know $5^2 = 25$, so $5^{-2} = \frac{1}{25}$

$$\boxed{\log_5\left(\frac{1}{25}\right) = -2}$$

Problem: Convert $4^3 = 64$ to logarithmic form.

The base stays the base. The result becomes the input. The exponent becomes the output.

$$\boxed{\log_4(64) = 3}$$

Problem: Convert $\log_7(343) = 3$ to exponential form.

$$\boxed{7^3 = 343}$$

Problem: Evaluate $\log(0.001)$

This is base 10 (common log). Ask: "10 to what power equals 0.001?"

$0.001 = \frac{1}{1000} = \frac{1}{10^3} = 10^{-3}$

$$\boxed{\log(0.001) = -3}$$

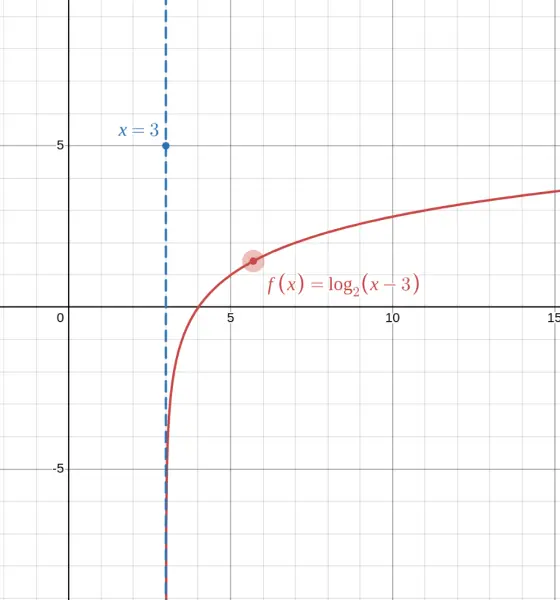

Problem: What is the domain of $f(x) = \log_2(x - 3)$?

The input to a logarithm must be positive:

$x - 3 > 0$

$x > 3$

$$\boxed{\text{Domain: } (3, \infty)}$$

Problem: Simplify $\log_4(4^7)$

Logarithm and exponential with the same base undo each other:

$$\log_4(4^7) = 7$$

$$\boxed{7}$$

Problem: Simplify $5^{\log_5(12)}$

Exponential and logarithm with the same base undo each other:

$$5^{\log_5(12)} = 12$$

$$\boxed{12}$$

Common Mistakes and Misunderstandings

❌ Mistake: Taking log of zero or negative numbers

Wrong: "$\log(-4) = ?$" or "$\ln(0) = ?$"

Why it's wrong: Logarithms are only defined for positive inputs. There's no real number $y$ such that $10^y = -4$ or $e^y = 0$.

Correct: The domain of any logarithm is $(0, \infty)$. If someone asks for $\log(-4)$, the answer is "undefined" (in the real numbers).

❌ Mistake: Forgetting that $\log_a(1) = 0$, not 1

Wrong: "$\log_5(1) = 1$"

Why it's wrong: $\log_5(1)$ asks "5 to what power equals 1?" Since $5^0 = 1$, the answer is 0.

Correct: $\log_a(1) = 0$ for any valid base $a$. Remember: any number to the zero power is 1.

❌ Mistake: Confusing $\log_a(x)$ with $\log(a) \cdot x$

Wrong: Treating $\log_2(8)$ as $\log(2) \times 8$

Why it's wrong: The subscript indicates the base, not multiplication. $\log_2(8)$ means "log base 2 of 8."

Correct: $\log_2(8) = 3$ because $2^3 = 8$. It has nothing to do with $\log(2) \times 8$.

❌ Mistake: Thinking $\log(a + b) = \log(a) + \log(b)$

Wrong: "$\log(3 + 5) = \log(3) + \log(5)$"

Why it's wrong: Logarithm of a sum does NOT split up. This is a common trap!

Correct: $\log(3 + 5) = \log(8) \approx 0.903$, but $\log(3) + \log(5) = \log(3 \times 5) = \log(15) \approx 1.176$. These are different!

The actual rule is: $\log(a \cdot b) = \log(a) + \log(b)$ (logarithm of a product splits into a sum).

❌ Mistake: Wrong direction when converting forms

Wrong: Converting $\log_3(81) = 4$ to "$3^{81} = 4$"

Why it's wrong: The number inside the log becomes the result of the exponential, not the exponent.

Correct: $\log_3(81) = 4$ converts to $3^4 = 81$. The base stays the base, the answer (4) becomes the exponent, and the input (81) becomes the result.

Summary: Exponentials vs. Logarithms

| Exponential $y = a^x$ | Logarithm $y = \log_a(x)$ |

|---|---|

| "Multiply repeatedly" | "What exponent?" |

| Domain: all real numbers | Domain: $(0, \infty)$ |

| Range: $(0, \infty)$ | Range: all real numbers |

| Horizontal asymptote: $y = 0$ | Vertical asymptote: $x = 0$ |

| Passes through $(0, 1)$ | Passes through $(1, 0)$ |

| Grows incredibly fast | Grows incredibly slowly |

| $a^0 = 1$ | $\log_a(1) = 0$ |

| $a^1 = a$ | $\log_a(a) = 1$ |

They are inverse functions — each undoes the other:

- $\log_a(a^x) = x$

- $a^{\log_a(x)} = x$

This skill is taught in the following courses. Create an account to access practice exercises and full course materials.