Logarithmic functions for Master Mathematics

The Spotify Problem

Imagine you're an engineer at a music streaming platform. Your boss wants a simple 5-tier ranking system for songs: Bronze, Silver, Gold, Platinum, and Diamond.

The data team reports that song play counts range from 1 play (your roommate's SoundCloud demo) to 10 billion plays (global mega-hits like "Blinding Lights").

"Easy," you think. "We'll divide it evenly — 2 billion plays per tier."

| Tier | Play Range |

|---|---|

| Bronze | 0 - 2 billion |

| Silver | 2 - 4 billion |

| Gold | 4 - 6 billion |

| Platinum | 6 - 8 billion |

| Diamond | 8 - 10 billion |

Then you test it:

- Your roommate's demo (12 plays) → Bronze

- A local band's regional hit (50,000 plays) → Bronze

- A chart-topping single (5 million plays) → Bronze

- A viral TikTok song (500 million plays) → Bronze

Wait... 99.9% of all songs are Bronze? The tier system is useless.

The problem: these play counts span 10 orders of magnitude (from 1 to 10,000,000,000). A linear scale crushes all the "small" values together.

The Fix: Think Multiplicatively

What if each tier represented a ×100 jump instead of a +2 billion jump?

| Tier | Play Range |

|---|---|

| Bronze | 1 - 100 plays |

| Silver | 100 - 10,000 plays |

| Gold | 10,000 - 1 million plays |

| Platinum | 1 million - 100 million plays |

| Diamond | 100 million - 10 billion plays |

Now:

- Your roommate's demo (12 plays) → Bronze

- Local band's regional hit (50,000 plays) → Gold

- Chart-topping single (5 million plays) → Platinum

- Viral TikTok song (500 million plays) → Diamond

Each tier represents a meaningful level of success. Going from 100 to 10,000 plays is the same "jump" as going from 1 million to 100 million — both are ×100.

This is logarithmic thinking. Instead of asking "how much more?", we ask "how many times more?"

The Connection to Exponentials

In the last lesson, you saw exponential growth: a penny doubled daily becomes $10.7 million. The question was "start with a base, apply the exponent, what do you get?"

But what if you flip the question?

Exponential: "A song has 10,000 plays. If plays increase 10× per tier, what tier is it?"

Logarithmic: "I know the result (10,000) and the multiplier (10). What's the tier number?"

That tier number — the exponent you need — is exactly what a logarithm tells you.

$$\log_{10}(10{,}000) = 4$$

The song is in tier 4. Logarithms answer: "What exponent do I need to reach this number?"

What is a Logarithm?

A logarithm answers the question: "What exponent do I need?"

$$\log_a(x) = y \quad \text{means} \quad a^y = x$$

Read $\log_a(x)$ as "log base $a$ of $x$."

The key insight: Logarithms and exponentials are two ways of expressing the same relationship:

| Exponential Form | Logarithmic Form | In words |

|---|---|---|

| $2^3 = 8$ | $\log_2(8) = 3$ | "2 to what power gives 8? Answer: 3" |

| $10^2 = 100$ | $\log_{10}(100) = 2$ | "10 to what power gives 100? Answer: 2" |

| $5^4 = 625$ | $\log_5(625) = 4$ | "5 to what power gives 625? Answer: 4" |

| $e^1 = e$ | $\ln(e) = 1$ | "e to what power gives e? Answer: 1" |

Think of it this way:

- Exponential: You know the exponent, you want the result

- Logarithm: You know the result, you want the exponent

The Two Most Important Logarithms

While you can have a logarithm with any positive base (except 1), two bases dominate:

Common Logarithm (Base 10)

$$\log_{10}(x) = \log(x)$$

When you see "$\log$" with no base written, it usually means base 10. This is the "common logarithm."

Why base 10? Because we use a decimal number system!

- $\log(10) = 1$ (one zero)

- $\log(100) = 2$ (two zeros)

- $\log(1000) = 3$ (three zeros)

- $\log(1{,}000{,}000) = 6$ (six zeros)

The common logarithm essentially counts "how many digits minus one" or "what order of magnitude."

Natural Logarithm (Base $e$)

$$\log_e(x) = \ln(x)$$

The natural logarithm uses base $e \approx 2.71828$ and is written as "$\ln$" (from the Latin logarithmus naturalis).

Why is this "natural"? In calculus, $\ln(x)$ has the beautiful property:

$$\frac{d}{dx}[\ln(x)] = \frac{1}{x}$$

No other logarithm has such a clean derivative. This makes $\ln(x)$ the go-to logarithm for calculus, just like $e^x$ is the go-to exponential.

Converting Between Forms

The ability to switch between exponential and logarithmic forms is essential. Practice this until it's automatic:

From Exponential to Logarithmic

$$a^y = x \quad \Longrightarrow \quad \log_a(x) = y$$

The base stays the base. The exponent becomes the answer. The result becomes the input.

Examples:

- $3^4 = 81 \quad \Longrightarrow \quad \log_3(81) = 4$

- $e^2 \approx 7.389 \quad \Longrightarrow \quad \ln(7.389) \approx 2$

- $10^{-1} = 0.1 \quad \Longrightarrow \quad \log(0.1) = -1$

From Logarithmic to Exponential

$$\log_a(x) = y \quad \Longrightarrow \quad a^y = x$$

Examples:

- $\log_2(32) = 5 \quad \Longrightarrow \quad 2^5 = 32$

- $\ln(1) = 0 \quad \Longrightarrow \quad e^0 = 1$

- $\log_5(125) = 3 \quad \Longrightarrow \quad 5^3 = 125$

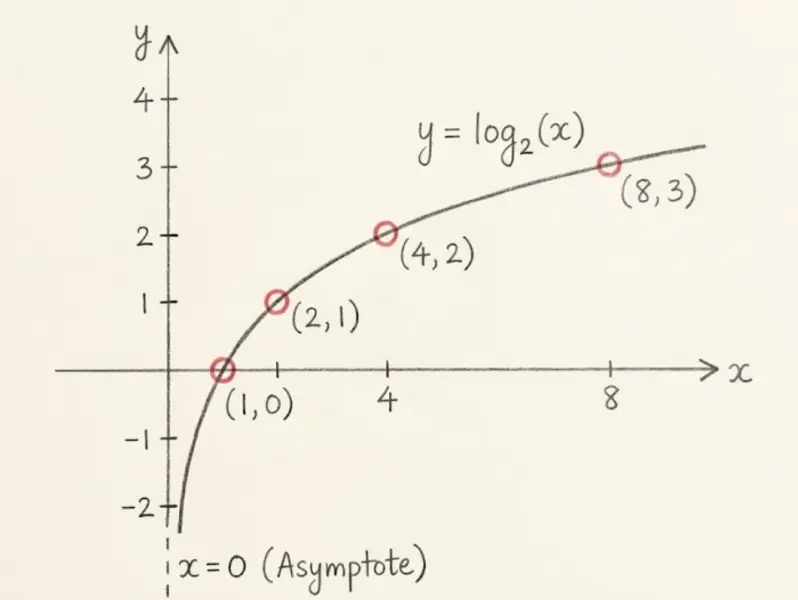

The Graph of a Logarithmic Function

Let's visualize $f(x) = \log_2(x)$ by building a table:

| $x$ | $\log_2(x)$ | Because... |

|---|---|---|

| 1/8 | -3 | $2^{-3} = 1/8$ |

| 1/4 | -2 | $2^{-2} = 1/4$ |

| 1/2 | -1 | $2^{-1} = 1/2$ |

| 1 | 0 | $2^0 = 1$ |

| 2 | 1 | $2^1 = 2$ |

| 4 | 2 | $2^2 = 4$ |

| 8 | 3 | $2^3 = 8$ |

| 16 | 4 | $2^4 = 16$ |

Notice the shape: it rises steeply at first, then grows more and more slowly. This is the opposite of exponential growth!

Logarithms and Exponentials are Inverses

Here's the profound relationship: logarithms and exponentials undo each other.

$$\log_a(a^x) = x \quad \text{and} \quad a^{\log_a(x)} = x$$

Think of it like this:

- $\sqrt{\ }$ undoes squaring: $\sqrt{x^2} = x$

- $\log_a$ undoes $a^x$: $\log_a(a^x) = x$

Graphically, this means the graphs of $y = a^x$ and $y = \log_a(x)$ are reflections of each other across the line $y = x$.

This reflection swaps:

- Domain and range

- Horizontal and vertical asymptotes

- The roles of $x$ and $y$

| Property | $f(x) = 2^x$ | $g(x) = \log_2(x)$ |

|---|---|---|

| Domain | All real numbers | $(0, \infty)$ |

| Range | $(0, \infty)$ | All real numbers |

| Asymptote | Horizontal: $y = 0$ | Vertical: $x = 0$ |

| Key point | $(0, 1)$ | $(1, 0)$ |

| Behavior | Always increasing | Always increasing |

Key Properties of Logarithmic Functions

For $f(x) = \log_a(x)$ where $a > 0$ and $a \neq 1$:

| Property | What it means |

|---|---|

| Domain | $(0, \infty)$ — only positive inputs! |

| Range | All real numbers — outputs can be anything |

| $x$-intercept | Always $(1, 0)$ because $\log_a(1) = 0$ |

| Vertical asymptote | $x = 0$ (approaches but never touches the $y$-axis) |

| Always increasing or decreasing | If $a > 1$: always increasing. If $0 < a < 1$: always decreasing |

| One-to-one | Each $y$ value comes from exactly one $x$ value |

Why can't we take the log of zero or negative numbers?

Think about it: $\log_2(0) = ?$ would mean $2^? = 0$. But no power of 2 ever equals zero!

And $\log_2(-8) = ?$ would mean $2^? = -8$. But $2^x$ is always positive!

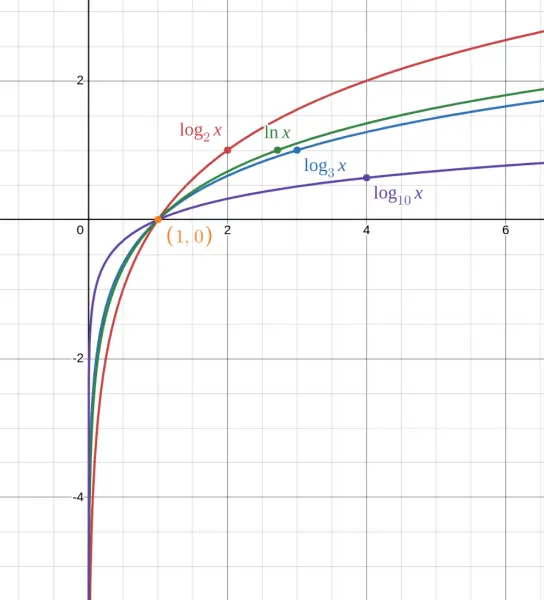

Notice that ALL these curves pass through $(1, 0)$. That's because $a^0 = 1$ for any positive $a$, so $\log_a(1) = 0$.

Special Values to Memorize

These show up constantly — know them cold:

| Expression | Value | Why |

|---|---|---|

| $\log_a(1)$ | $0$ | Because $a^0 = 1$ |

| $\log_a(a)$ | $1$ | Because $a^1 = a$ |

| $\log_a(a^n)$ | $n$ | Logarithm undoes the exponential |

| $\ln(1)$ | $0$ | Because $e^0 = 1$ |

| $\ln(e)$ | $1$ | Because $e^1 = e$ |

| $\log(10)$ | $1$ | Because $10^1 = 10$ |

| $\log(100)$ | $2$ | Because $10^2 = 100$ |

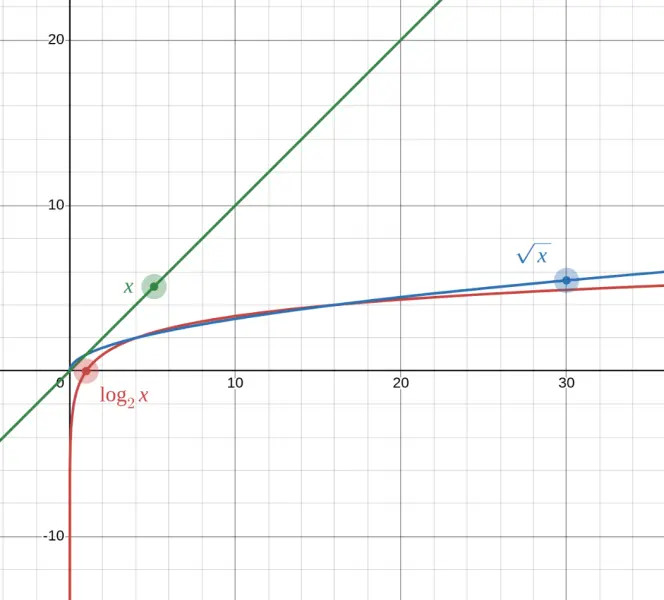

Logarithmic vs. Exponential Growth

Logarithms grow incredibly slowly compared to other functions.

| $x$ | $\log_2(x)$ | $\sqrt{x}$ | $x$ |

|---|---|---|---|

| 4 | 2 | 2 | 4 |

| 16 | 4 | 4 | 16 |

| 256 | 8 | 16 | 256 |

| 65,536 | 16 | 256 | 65,536 |

| 1,000,000 | ~20 | 1,000 | 1,000,000 |

To get $\log_2(x) = 20$, you need $x = 2^{20} = 1{,}048{,}576$ — over a million!

This slow growth is actually useful! It's why we use logarithmic scales:

- Decibels (sound intensity) — lets us compare a whisper to a jet engine

- Richter scale (earthquakes) — a magnitude 8 is 10× more intense than magnitude 7

- pH scale (acidity) — each unit is a 10× change in hydrogen ion concentration

Why Logarithms Matter in Real Life

The Decibel Scale

Sound intensity varies enormously. A jet engine is about 1,000,000,000,000 times more intense than the quietest sound you can hear. That's unwieldy!

Instead, we use decibels: $dB = 10 \log\left(\frac{I}{I_0}\right)$

| Sound | Intensity ratio | Decibels |

|---|---|---|

| Threshold of hearing | 1 | 0 dB |

| Whisper | 100 | 20 dB |

| Normal conversation | 1,000,000 | 60 dB |

| Jet engine | 1,000,000,000,000 | 120 dB |

Logarithms compress huge ranges into manageable numbers!

The Richter Scale

Earthquake magnitude: $M = \log\left(\frac{A}{A_0}\right)$

Each whole number increase means 10× more ground shaking. A magnitude 8 earthquake releases about 32 times more energy than a magnitude 7.

Computer Science

Logarithms appear everywhere in algorithms:

- Binary search takes $\log_2(n)$ steps to find an item in a sorted list of $n$ items

- Efficient sorting algorithms take about $n \log(n)$ operations

If you have 1 billion items, binary search finds any item in about $\log_2(1{,}000{,}000{,}000) \approx 30$ steps. That's the power of logarithmic efficiency!

Practice: Evaluate and Convert

Problem: Evaluate $\log_3(81)$

Ask yourself: "3 to what power equals 81?"

$3^1 = 3$ $3^2 = 9$ $3^3 = 27$ $3^4 = 81$ ✓

$$\boxed{\log_3(81) = 4}$$

Problem: Evaluate $\log_5\left(\frac{1}{25}\right)$

Ask: "5 to what power equals $\frac{1}{25}$?"

We know $5^2 = 25$, so $5^{-2} = \frac{1}{25}$

$$\boxed{\log_5\left(\frac{1}{25}\right) = -2}$$

Problem: Convert $4^3 = 64$ to logarithmic form.

The base stays the base. The result becomes the input. The exponent becomes the output.

$$\boxed{\log_4(64) = 3}$$

Problem: Convert $\log_7(343) = 3$ to exponential form.

$$\boxed{7^3 = 343}$$

Problem: Evaluate $\log(0.001)$

This is base 10 (common log). Ask: "10 to what power equals 0.001?"

$0.001 = \frac{1}{1000} = \frac{1}{10^3} = 10^{-3}$

$$\boxed{\log(0.001) = -3}$$

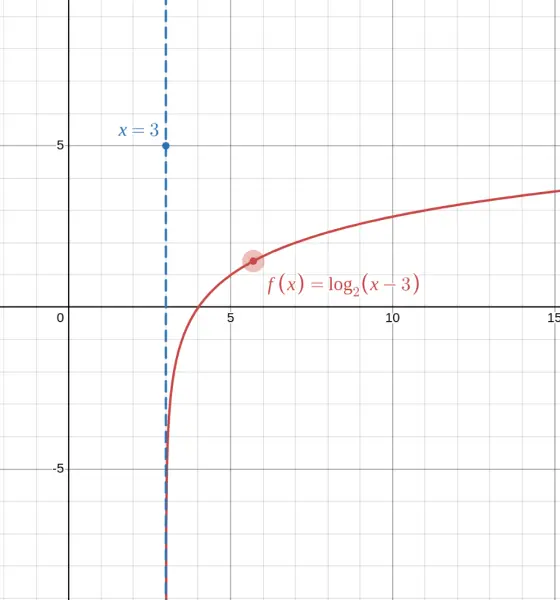

Problem: What is the domain of $f(x) = \log_2(x - 3)$?

The input to a logarithm must be positive:

$x - 3 > 0$

$x > 3$

$$\boxed{\text{Domain: } (3, \infty)}$$

Problem: Simplify $\log_4(4^7)$

Logarithm and exponential with the same base undo each other:

$$\log_4(4^7) = 7$$

$$\boxed{7}$$

Problem: Simplify $5^{\log_5(12)}$

Exponential and logarithm with the same base undo each other:

$$5^{\log_5(12)} = 12$$

$$\boxed{12}$$

Common Mistakes and Misunderstandings

❌ Mistake: Taking log of zero or negative numbers

Wrong: "$\log(-4) = ?$" or "$\ln(0) = ?$"

Why it's wrong: Logarithms are only defined for positive inputs. There's no real number $y$ such that $10^y = -4$ or $e^y = 0$.

Correct: The domain of any logarithm is $(0, \infty)$. If someone asks for $\log(-4)$, the answer is "undefined" (in the real numbers).

❌ Mistake: Forgetting that $\log_a(1) = 0$, not 1

Wrong: "$\log_5(1) = 1$"

Why it's wrong: $\log_5(1)$ asks "5 to what power equals 1?" Since $5^0 = 1$, the answer is 0.

Correct: $\log_a(1) = 0$ for any valid base $a$. Remember: any number to the zero power is 1.

❌ Mistake: Confusing $\log_a(x)$ with $\log(a) \cdot x$

Wrong: Treating $\log_2(8)$ as $\log(2) \times 8$

Why it's wrong: The subscript indicates the base, not multiplication. $\log_2(8)$ means "log base 2 of 8."

Correct: $\log_2(8) = 3$ because $2^3 = 8$. It has nothing to do with $\log(2) \times 8$.

❌ Mistake: Thinking $\log(a + b) = \log(a) + \log(b)$

Wrong: "$\log(3 + 5) = \log(3) + \log(5)$"

Why it's wrong: Logarithm of a sum does NOT split up. This is a common trap!

Correct: $\log(3 + 5) = \log(8) \approx 0.903$, but $\log(3) + \log(5) = \log(3 \times 5) = \log(15) \approx 1.176$. These are different!

The actual rule is: $\log(a \cdot b) = \log(a) + \log(b)$ (logarithm of a product splits into a sum).

❌ Mistake: Wrong direction when converting forms

Wrong: Converting $\log_3(81) = 4$ to "$3^{81} = 4$"

Why it's wrong: The number inside the log becomes the result of the exponential, not the exponent.

Correct: $\log_3(81) = 4$ converts to $3^4 = 81$. The base stays the base, the answer (4) becomes the exponent, and the input (81) becomes the result.

Summary: Exponentials vs. Logarithms

| Exponential $y = a^x$ | Logarithm $y = \log_a(x)$ |

|---|---|

| "Multiply repeatedly" | "What exponent?" |

| Domain: all real numbers | Domain: $(0, \infty)$ |

| Range: $(0, \infty)$ | Range: all real numbers |

| Horizontal asymptote: $y = 0$ | Vertical asymptote: $x = 0$ |

| Passes through $(0, 1)$ | Passes through $(1, 0)$ |

| Grows incredibly fast | Grows incredibly slowly |

| $a^0 = 1$ | $\log_a(1) = 0$ |

| $a^1 = a$ | $\log_a(a) = 1$ |

They are inverse functions — each undoes the other:

- $\log_a(a^x) = x$

- $a^{\log_a(x)} = x$

This skill is taught in the following courses. Create an account to access practice exercises and full course materials.